Scope Of Patent Invention Extensible Under “Doctrine Of Equivalents”Ball Spline Case

About Ball Spline Bearing

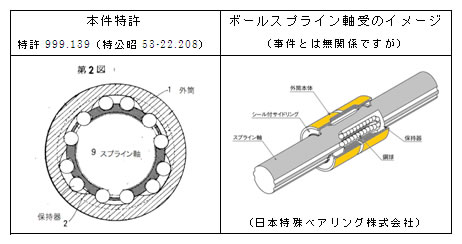

The patent right at issue was claimed for the invention, “ball spline bearing.”

The invention is a bearing capable of moving along a shaft in a longitudinal direction while making a torque transmission. The bearing is used for e.g. a vehicle’s axle shaft. This invention is more complicatedly configured such that balls can circulate in a plurality of serially-connected grooves formed in parallel with a spline axis.

Background Of Case

The patentee obtained a patent right with respect to the invention entitled “ball spline bearing for infinite sliding” (Patent No. 999,139 (Publication No. S53-22208). The patented invention includes: 1) an outer tube 1; 2) a holder 2 configured to hold balls; and 3) a rotatable spline shaft 9. On the other hand, the alleged infringer manufactured and sold similar products since about January 1983.

Judgment Of High Court

The District Court held that the defendant’s product did not fall within the technical scope of the patent, and therefore, did not infringe upon the paten right. The defeated patentee filed an appeal with the High Court.

1) Not precisely identical

The High Court held that the appellee’s product was obviously different in part from the patented invention.

2) Obviousness of replacement

As to a different part of the claimed elements, it was determined that:

- A difference between a part of the claimed elements and that of the accused product does not achieve any particular effects.

- The different part is interchangeable with, and could have easily been replaced with that of the accused product in light of the technical level at the time of filing of the patent application.

- It should be appropriate to determine, by way of exception, that the accused product is regarded as falling within the technical scope of the patented invention, and therefore, infringes upon the patent right.

- Otherwise, the patent right granted in compensation for the publication of the invention would be meaningless, which conflicts with the goal of the patent system.

In such a manner, the patentee (the appellant) prevailed in the High Court’s judgment.

Final Appeal To Supreme Court

The alleged infringer (the appellee) filed a petition of final appeal with the Supreme Court on the grounds of erroneous construction or application of the Patent Act. The Supreme Court having discretionary jurisdiction over such a petition of final appeal is not supposed to accept all the complaints. Hereinafter, explanations will be made about the Court’s opinion on the “doctrine of equivalents,” which is of great value, by placing it above the main text of decision.

1) Doctrine of equivalents

The author (Mr. Sakuo Yamaguchi, Japanese patent attorney) is reminded that, some decades ago, the meaning of “doctrine of equivalents” was shallowly understood in Japan, and there was a tendency to try to extend the scope of a patent right by puzzlingly emphasizing e.g. “equivalents to・・・” when the accused product and the patented claim were not precisely identical in elements to each other.

At that time, in a situation where a plaintiff had submitted an expert’s opinion referring to the doctrine of equivalents in a manner similar to the above, the author questioned the expert in the witness-examination.

[Author]: “According to your submitted expert opinion, the accused product is ‘equivalents’ to the patented invention, isn’t it?”

[Expert]: “Yes, it is. The defendant’s conduct of selling infringes upon the patent right.”

[Author]: “In that case, I have further questions about the fullest extent to which the doctrine of equivalents can be applied. It is not allowed to limitlessly extend the technical scope merely by emphasizing ‘equivalents to・・・’, isn’t it?”

[Expert]: “・・・・・・”

[Author pretending to be surprised]: “Did you really submit this expert opinion without knowledge of the limitation to the doctrine of equivalents (such as an intentionally removed element in the amendments)?”

(Such a matter had already been written in Mr. Yoshifuji’s textbook).

In such a manner, a few decades ago in Japan, the “doctrine of equivalents” was confusingly understood due to its insufficient organization.

This doctrine was clarified by the Supreme Court’s decision.

2) Five requirements for equivalents

It was explicitly held that, in principle, if there is any claimed element different from the corresponding structure of the accused product, such an accused product does not fall within the technical scope of the patented invention.

It was confirmed, however, that, even if there is any claimed element different from the corresponding structure of the accused product, such an accused product may fall within the technical scope as equivalents to the claimed invention if the following conditions are met:

- The different element is not an essential part of the patented invention.

- In spite of the different element, the accused product and the patented invention are identical to each other in the attained objective and the achieved effects.

- A PHOSITA could have easily come up with the idea of replacing the different element with the corresponding structure of the accused product at the time of the manufacture of the accused product (not at the time of filing of the patent application).

- However, the accused product is not identical to well-known art or could not have easily been reached by a PHOSITA based upon such a well-known art at the application time (the time of filing of the patent application). If the accused product is identical to well-known art or could have easily been reached by the PHOSITA, the relevant invention should not have been granted patent.

- There is not any particular circumstance where the accused product is intentionally removed from the technical scope of the claimed invention during the prosecution.

3) Grounds for five requirements

The above requirements were confirmed on the following grounds:

- It is difficult to draft claims to cover all the future possible infringing embodiments when filing a patent application. If an opposite party avoids a patent infringement merely by replacing a part of the claimed elements with that developed after the patent application, incentive for innovation would be reduced, which conflicts with the goal of the patent system and the sense of justice in the society.

- In view of such points, a substantial value of a patented invention should extend to a technique that could have easily been come up with by third parties from the structures recited in a claim as a technique that is substantially identical to the claimed invention.

- A technique that is well-known art or could have easily been come up with by a PHOSITA at the application time of the invention should not have been granted patent, and therefore, the scope of the patented invention should not extend to such a technique.

- Under the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel, a patentee is not allowed to make any assertion on the matter for which the patentee admitted by the behavior of an applicant that it does not fall within the technical scope, for example, the matter having been intentionally removed by the applicant from the technical scope of the claimed invention during the prosecution.

4) Which prevailed?

The requirements for applying the doctrine of equivalents to be kept in mind for the future use are organized in the above manner. In this patent-right infringement litigation, the main text of decision was different from the organization of the doctrine of equivalents.

Whether the “obviousness of replacement” was proved or not was the point at issue. The patentee had attempted to argue that the idea of replacing the different element of the claim with the corresponding structure of the accused product could have easily been come up with by a PHOSITA. For this purpose, the patentee submitted the patent publications previously published in Japan, Germany, and the U.S. to prove that the accused product had been merely a result obtained by combining well-known arts at the time of filing of the patent application (!) relying upon the submitted publications.

In that case, it was determined by the Supreme Court that, in view of the patentee’s submitted publications, the accused product had been merely the result obtained by combining the well-known arts at the time before filing of the patent application, and that, if a PHOSITA could have easily reached such a combination without knowledge of the patented invention, the accused product had been a product that could have easily been come up with at the application time based upon the arts known before the application time. It was further determined that the invention should not have initially been granted patent, and therefore, the scope of the invention should not extend to the accused product. The patentee was reversely defeated in the Supreme Court’s decision.

Erroneous Construction Of Patent Act

As mentioned above, the High Court examined the interchangeability and the obviousness of replacement, but determined that the accused product falls within the claim scope under the doctrine of equivalents without examining any relation between the accused product and the publications of well-known arts.

By indicating the above points, the Supreme Court held that the judgment of the High Court was unlawful for erroneous construction or application of the relevant act, inexhaustive examination, and absence of reasons, and such unlawfulness would obviously sway the High Court in the judgment, and concluded that this case should be remanded to the High Court.

If you have any questions concerning the above, please feel free to contact us by sending email to inter@ypat.gr.jp.